Cycling to extremes: Heart health and endurance sports

Posted on February 3rd, 2017 by Andries Lodder

Are endurance athletes hurting their hearts by repeatedly pushing beyond what is normal?

The sun was bright upon the upturned redrock Flatirons above Boulder, Colorado. It was a beautiful July morning in 2013. Lennard Zinn, a world-renowned technical cycling guru, founder of Zinn Cycles, longtime member of the VeloNews staff, lover of long rides, and a former member of the U.S. national cycling team, was riding hard up his beloved Flagstaff Mountain, a ride he had done a thousand times before. But this time, it was different.

His life was about to change forever.

When his heart began to flop like a fish in his chest, and his heart rate jumped from 155 to 218 beats per minute and stayed pegged there, his first reaction was simple: “I went into denial.”

He arrived to the ER that afternoon and was later brought via ambulance to the main cardiac unit for an overnight stay. Though he trusted the cardiologists and the ER doctor, he doubted their warnings. His denial was strong.

After following their recommendations for rest, he returned to training; the electrodes glued to his chest and the telemetric EKG unit dangling around his neck didn’t disrupt his routine. But the annoying episodes happening with increasing frequency during his more intense rides did. The flopping fish would return as his heart rate spiked. More upsetting was the phone call in the middle of the night from a faraway nurse who had been watching his EKG readings and had some shocking news: His heart had stopped for a few seconds.

By October, Zinn received an official diagnosis: multifocal atrial tachycardia. Normally, the heart rate is controlled by a cluster of cells called the sinoatrial (SA) node. When a number of different clusters of cells outside the SA node take over control of the heart rate, and the rate exceeds 100 beats per minute, this is called multifocal atrial tachycardia (AT).

“That’s when I decided to take the warning I’d been given and quit racing,” he said.

Zinn was instantaneously downgraded from thoroughbred to invalid. He has had to back off from riding with intensity, or duration. He has had to alter his life, in more ways than one. He has had to face the fact that he can never do what he used to do, in the same way that he used to do it. Life has changed. Forever.

Was his bike trying to kill him?

Zinn is not alone. When he began his arduous reconciliation with his life-changing condition, he began reaching out to others from his generation that were fabulous athletes in their day, and who continued to push themselves well into their 40s and 50s.

The number of friends and former teammates that had similar or more severe heart issues was disconcerting. Far from being an outlier, Zinn was one among many.

Mike Endicott was one of those friends. He had been interested in endurance sports since he was a teenager.

“By nature I’m a person who likes to train,” Endicott said. “I race to train; a lot of people train to race. That was kind of anti-climactic. I use racing as kind of a gauge as to where you’re at, but I much prefer to be just out doing stuff. I just like the movement and activity, being outside.”

His interests evolved so that six months of the year he would be Nordic skiing, and the other six months would be devoted to riding road and mountain bikes. It was non-stop. Meanwhile, he was expanding his business as an independent sales representative across the Rocky Mountain West.

“I was burning the candles at both ends,” Endicott said. “I was having a ball. I was working, I was making a good living, but boy was I burning it and I didn’t realize it.”

Then, one day in 2005, he headed to a Nordic ski race at Devil’s Thumb Ranch, an area in the Fraser Valley of Colorado. In a familiar tale, Endicott’s life was about to change forever.

“I had created the perfect storm over a good 20-year period, but it all came to a head here because of the week or two prior to this race,” he said.

With a stressful week of travel leading up to the event, Endicott hadn’t slept well the night before. But, like so many of us, he just enjoyed being out there. He didn’t eat much before the race except for two big coffees, and an hour before the race downed a few caffeinated energy gels. The temperature was around zero degrees, overcast, with light snows falling and a bit of a breeze swirling around. The conditions for the perfect storm had fallen into place.

“I’m having a good race, I was having fun, going after it,” he recalled. “I punched up over this rise and all of a sudden, I don’t feel good, something’s not right. Something was beating inside my chest. No pain, no discomfort, but I was a little dizzy.”

He felt like he was drunk. He could hardly stay up on his legs. He would collapse and get back up, his heart still doing something strange inside his chest. By the time the last skiers of the field passed by, Endicott was done. He collapsed in the snow and began to die. He was on his back, barely maintaining consciousness, in a skin suit, in the snow, in zero-degree weather. There was no pain, but he couldn’t catch his breath. He tried to yell for help, but he’d barely make a noise. He could only wave his pole.

“Fairly quickly I learned I’m in deep shit here. Basically, I figured I was done, this was it,” he said. “It’s interesting; at the time, my emotions were… I was frustrated. It was not on my list of things to do because I was kind of a type-A. My dog was in my truck, we were going to go out and do a ski when I was done, I had work to do that afternoon, phone calls. It just wasn’t on my list of things to do, to die on the ski trails. I was pissed [laughs]. I was beating on my chest with my hands saying, ‘Come on, something’s got to work here.’ So I struggled in and out of consciousness out there in the snow for about an hour. I don’t know how long I was out, and then I’d come back again, and then I’d try to look around and then I’d get dizzy again. It was ugly.”

By chance, two of his friends who had gone out for a cool down after their race saw Endicott wave his arm out of the corner of their eyes, and skied to find a fallen friend dying in the snow.

Endicott was in ventricular tachycardia (VT or V-tach); the result was sudden cardiac death, an immediate, unexpected loss of heart function, breathing, and consciousness. Just 50 at the time, Endicott miraculously survived, resuscitated on the scene. But his life is very different now.

THE HEART OF THE MATTER

Cycling is an endurance sport like no other. Long rides can be a standard component of the diet, something that devotees look forward to all week. In any case, as a cyclist, you likely love the weekend rampage, the six-hour tour of the mountains, or the endless training sessions that are the only way to develop fitness for races that last as long as a workday. But fit for racing doesn’t necessarily equal healthy.

Stories abound that undermine the notion that elite athletes are healthy. From the running world, marathoner Alberto Salazar, at the age of 48, suffered a heart attack and lay dead for 14 minutes before a cardiologist placed a stent in a blocked artery, saving his life. Micah True, the ultra-marathoner and protagonist of the bestselling book Born to Run, went for a 12-mile run in the New Mexico wilderness and was later found dead.

Of course, these tragic tales are preceded by the origin story of an endurance athlete running himself, literally, to death. An enlarged, thickened heart with patchy scar tissue is common in long-term endurance athletes and is dubbed “Pheidippides cardiomyopathy” after the 40-year-old running messenger (and prototypical masters endurance athlete) who died after bringing the news of Greek victory at the battle of Marathon to Athens. Pheidippides was a hemerodrome, (an all-day running courier in Ancient Greece), and he had run 240km over two days to request help from Sparta against the Persians at Marathon, before expiring after running the additional 42km (26.2 miles) back from the battlefield. We celebrate his death by running marathons.

These deaths are even more alarming when you consider the subjects — highly trained athletes in what many would consider peak physical condition. Isn’t exercise supposed to prevent us from falling to a heart attack?

In recent years, cardiologists who have studied extreme exercise and its side effects have proposed a hypothesis that suggests these tragedies may not be so shocking after all. There can be too much of a good thing when it comes to your heart.

That organic metronome in your chest, rhythmically coordinating 100,000 beats per day without pause, takes the brunt of the abuse in endurance athletes. When you’re seated, it pumps about five quarts of blood per minute. When you’re running, that figure bounds to 25 to 30 quarts. The human heart wasn’t designed to handle that load for hours on end, day after day.

In the case of endurance athletes who have competed for years — whose hearts have exceeded the threshold of normal heart rates for decades — going above what is normal defines them. But it may also be killing them.

To understand why, it helps to know the mechanisms of the heart. There are two systems at play: the plumbing and the electronics. We’ll begin with the pipes.

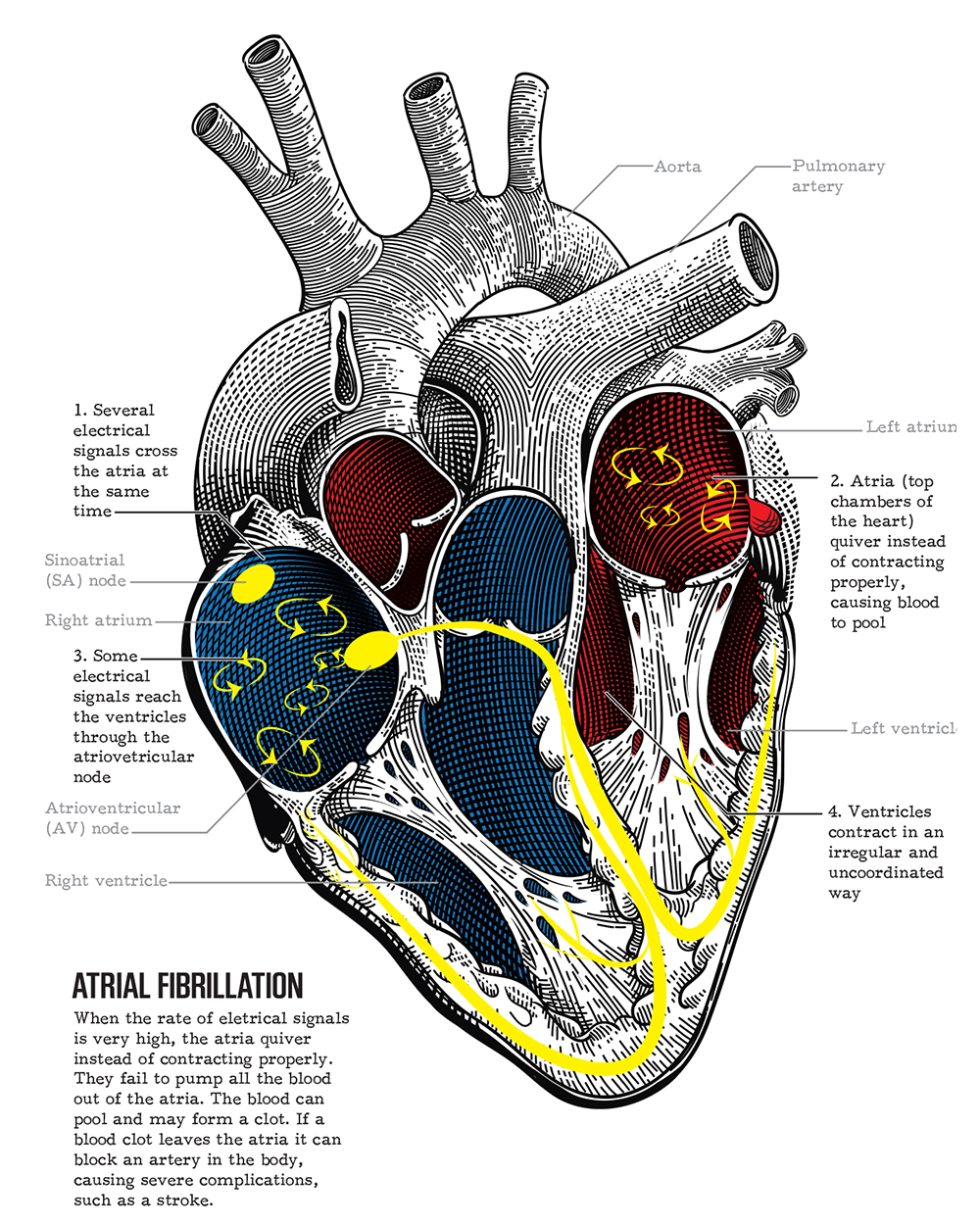

The heart’s right side pumps deoxygenated blood from the body to the lungs, and the left side pumps oxygenated blood from the lungs to the body. Each side has two chambers, a small one called the atrium and a large one called the ventricle. When the heart contracts, everything moves in a coordinated fashion, with the atria contracting first and the ventricles following. The blood is pushed through the heart into either the vascular system in the lungs or the body.

For one out of every five people with heart disease, the first sign is sudden cardiac death. However, sudden cardiac death during an athletic undertaking is, in general, very rare. In some cases it can be due to heart attack — myocardial infarction — caused by lifestyle diseases such as atherosclerosis, which can lead to blockages.

But various forms of arrhythmia (abnormal heart rhythms) are trickier. This is where the electronics come in. They may have a genetic component, but they can also be influenced by stress and intense training. Arrhythmia is a generic label for a condition in which the heart rhythm is altered from its common pattern in various parts of the heart. These episodes can be more or less dangerous depending on their speed, how long they last, and which part of the heart they affect.

When we train intensively for an endurance event, several adaptations occur in our hearts. The most common is that our resting heart rate goes down due to improved heart function. Many endurance athletes will experience what they think is the sensation of their hearts skipping a beat. Actually, this is most often due to premature beats — a premature ventricular contraction (PVC) if it originates in the ventricle or a premature atrial contraction (PAC) if it originates in the atrium. Both PACs and PVCs are quite common in well-trained athletes and often are not dangerous.

OVERDOSE

With the growth of endurance sports (the number of licensed bike racers in the U.S. increased by 15 percent between 2009 and 2013, according to USA Cycling; the number of runners has grown 70 percent over the past decade, according to the National Sporting Goods Association), there has been an increase in interest to the potential adverse acute effects of long and intense training and racing on the heart. Endurance athletes endure fluid shifts, changes in pH and electrolytes, and fluctuations in blood pressure. Their atria are exposed to chronic volume and pressure overload. The athlete’s heart lurches from extreme to extreme — from spikes approaching 200bpm to long periods of ultra-low resting heart rates below 60bpm, a condition called bradycardia.

The heart adapts to this by growing larger, contracting with more strength, and responding more vigorously to adrenaline. We call this fitness. Whether or not it’s also healthy is up for debate.

Does the scientific community have a solid definition for what an endurance athlete is? How many hours it takes per week or month to go from part-time participant to all-out endurance junkie? “Hell no,” said Dr. John Mandrola, a heart-rhythm doctor from Louisville, Kentucky, who takes a keen interest in the hearts of endurance athletes, and who is himself a cyclist with atrial fibrillation (AF). “What’s too much? That’s the $64,000 question. Though I will say it’s a little like what the judge said about indecency: ‘I know it when I see it.’”

Endurance athletes push so far beyond what has historically been considered normal that their hearts can show signs that mimic disease. Abnormal heart rhythms would usually be cause for concern. But trained athletes experience a host of benign irregularities, including premature beats, those PACs and PVCs. Most of them remain simple nuisances, and, more often than not, rest increases their frequency.

As for electrical abnormalities, the data speaks for itself. Long-term endurance exercise results in a five-fold increase in the risk of developing AF. A review of the relevant research finds many small studies that correlate long-term sports activity with AF (incidentally, Robert Gesink of Lotto-JumboNL had surgery in May 2014 for atrial fibrillation and has returned to the sport). Though none is conclusive, collectively they indicate a pattern: “Younger patients with a lower cumulative dose of exercise have lower AF risk. Older patients with higher dosages of exercise have higher AF risk,” Mandrola said.

“[People] criticize the studies that have been done that make this association. And they have a point: Each of the studies, individually, has flaws. They’re from one center, they include small numbers of athletes, and there’s selection bias. But taken together — there’s maybe ten to 20 single-center studies that show this association. If you put all that evidence together, there’s reason to believe that endurance athletes can develop AF.”

Perhaps the most influential study on mechanisms of AF in athletes comes from the study of rats and the effects of endurance exercise on the atria, conducted by a group of Spanish researchers and published in the journal Circulation in 2010. Rats were run one hour per day, five days a week, for up to 16 weeks. And they paid. Compared with sedentary controls, the exercised rats displayed evidence of damage, things such as enhanced vagal tone, atrial dilation, atrial fibrosis, and vulnerability to pacing-induced AF. Detraining the rats quickly led to a reduction in the vulnerability of AF, but not structural changes. Fibrosis and left atrial dilation remained after the rats stopped exercising. Is this what is happening inside your chest when you repeatedly go out and ride your bike, before work, after work, and every weekend in the summer?

“Look at some of the science that’s been done and think about what an endurance athlete has to go through,” Mandrola said. “They have a high cardiac output, their heart is exposed to high volume, high pressure, intense electrical and adrenaline stimulation, but then they also develop slow heart rates. So it’s this combination of spikes in adrenaline and pushing through that red zone combined with always having a slow heart beat. If you look at the plausibility side, it is plausible. When you have the experience I have as a physician, as a heart rhythm doctor, there are definite patterns of Zinn-like people, and me, and others who get this, and they have nothing else that could have caused it. They don’t have high blood pressure, they don’t have diabetes, they’re not fat, and most don’t drink alcohol excessively. So most of these things that lead to heart rhythm problems, the endurance athlete doesn’t have. The only thing is the endurance exercise — too much endurance exercise over too long of a time period.”

The more you ride, the harder you ride, the faster you ride, the better athlete you might become today. But over decades of exertion, the myocardial cells of the heart begin to simply fall apart, and you’re left with an unhealthy ticker. Or so these new studies suggest. When you’re 20, or even 30, this can lead to acute reversible injuries — temporary damage that can be relieved with correct rest. In a 50-year-old, repeated hard doses of the sport you love, the rides you cherish — since complete recovery doesn’t occur as efficiently — could be leading to accelerated aging, or hypertrophy — in layman’s terms, a stiff muscle in your chest. That probably wasn’t what you were looking for when you bought your last bike. One of the more telling research papers on the subject, published in 2011 in the Journal of Applied Physiology, studied the structure and function of the heart in lifelong competitive endurance veteran athletes, ranging in age from 50 to 67. MRI studies revealed that some 50 percent of the veteran athletes had myocardial fibrosis, a condition that involves the impairment of the heart’s muscle cells, called myocytes, through hardening or scarring of tissue. In age-matched controls — people of the same age who didn’t compete — and young athletes, there were zero cases of the disease. Furthermore, the fibrosis was significantly associated with the number of years spent training, and the number of marathons and ultra-endurance marathons they had completed.

Other studies have shown that Tour de France riders and other former professional athletes live lon- ger than average, and often have lower rates of heart issues later in life. Maybe that sounds counterintuitive, because often these athletes are riding in volumes that far exceed even those of the most addicted masters endurance athlete. But there’s a key difference. The pro athletes did it, then quit and didn’t continue to do it later in life. Masters athletes? They just keep plugging away, with the mindset that if they train like Contador, they’ll be able to ride like Contador. Year after year, decade after decade, it adds up.

Still, there is no arguing that physical activity is an effective, efficient, and virtually incomparable way to care for your heart, fight cardiovascular disease, and prolong your life. For every journal article that says endurance athletics is hurting their heart, there is one that says the opposite. Or maybe two.

But, like many other medicines, more isn’t always better. Research is honing in on the issue of dosage in exercise. If you think of exercise as a drug, there is a certain threshold at which good becomes bad, when benefit becomes detriment. When is too much? Is everyone the same, or are some predisposed to risks of extreme exercise? Is intensity as bad as duration, or duration as bad as intensity? Is it only bad if repeated over years or decades? The science is new when it comes to the science of overdosing on exercise.

THE PERFECT STORM

Doctors immediately ruled out any plumbing issues in Endicott’s heart. Had he gone to the Mayo Clinic the day before the race, it’s more than likely that nothing would have ever shown up on paper, on any test, that would have led the doctors to stop him from racing.

“They would have pronounced me healthy as a horse,” he said. “The EKG would have been perfect because I wasn’t having any symptoms. Nothing was symptomatic whatsoever. No PVCs, no weird rhythms. Everything on paper [was fine], with the exception of a little bit of artery disease — not much more than a lot of people that age.”

After looking at a lot of different cases and talking to a lot of different doctors, Endicott has concluded that this was all his fault. “Yeah, I did all this to myself — by personality. And if someone would have gone to me before this happened — and this is a key part of reality — and said you need to back off because this is your future, would I have changed anything? Probably not. I would likely do the same activities, but I would rest and recover more. Just because that’s the nature of a lot of us. We enjoy doing it, we’re probably doing it too much, we’re selfish about it, and we’re going to be in denial, and that’s a problem that a lot of these electrophysiologists have when we ask ‘Why me?’”

The most difficult component to life after heart malfunction, at least for many, is the psychological struggle.

One of the problems with a lot of athletes — the problem with Endicott — is that they can’t stop asking “why.” How could this happen to someone who has built his life around being active? It just doesn’t make sense.

Patients naturally want to find out what went wrong when they’re meeting with their cardiologist. They want the doctor to help solve the puzzle. But physicians don’t like to speculate. The doctor’s job is to stabilize a patient, keep them alive, and try to give them quality of life. Nowhere in the patient-doctor relationship is there an agreement that the patient won’t go out and race again, or compete in gran fondos, marathons, or triathlons.

But going to the hospital again and again for repeated invasive procedures until doctors settled on a long-term — and uncomfortable — solution. In Endicott’s case, that meant having not one, but three failed ablations (four in total).

Cardiac arrhythmias can be mapped by stimulating the heart with adrenaline in the operating room and following the aberrant circuitry with a catheter electrode. The tissue through which that current is flowing can then sometimes be destroyed with RF radiation or cryogenics from another catheter; this is called cardiac ablation.

Because Endicott’s tachycardia was exercise-induced, he would not only need to be awake for the procedure, but would be caffeinated and given intravenous adrenaline so as to improve the chances of inducing arrhythmia while he was on the table.

The first attempt failed to stabilize him after an eight-hour session. The next time he spent 16 hours on the table. Still, physicians couldn’t induce tachycardia. Eventually, it was determined that he was too high risk not to have an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) since he was going out and still doing the things he loved to do, which was leading to more episodes of VT.

The ICD can be a beautiful device, shocking the heart back into rhythm, saving a life from the inside out. But it isn’t without its discomforts. It is, according to Endicott, like getting hit by lightning. If you’re on a bike when it happens, it’s going to knock you off. When the device determines that the rhythm is out of synch, it establishes what kind of rhythm is needed, and then it momentarily re-boots you. Your heart stops, so it can restart with the correct rhythm.

It may sound like a miracle, and it can be. But it can also lead to catastrophe, in what is called an electrical storm. Endicott suffered such a storm when he was performing as a member of a band at a retirement community. His instrumental solo bumped his level of adrenaline, and he went into V-tach.

“I would go into V-tach, I would get the shock [from the ICD], and the adrenaline, the shock, would convert me into sinus rhythm for a couple of beats, but there was so much adrenaline that I would get thrown right back into V-tach. This is a cycle, and it was brutal. [The ICD] is going to do its job until I’m dead,” Endicott recalled. “We’re talking about something that feels like 1,000 volts. It happens quickly but you’ll see a flash… It was basically like being tortured,” he said.

He had only one to one and a half minutes between shocks. When the paramedics arrived he was still convulsing. He had suffered through 32 consecutive shocks from the ICD. The result was an acute case of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Finally, in 2009, Endicott was referred to the cardiology department at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. Their top electrophysiologist, Dr. William Stevenson, reviewed the case and decided to try one more ablation. It worked in four hours, after it was discovered that the bad circuitry was on the outside of the heart, rather than inside, which is most typical.

Zinn hasn’t been so lucky. His first — and so far only — ablation attempt failed. Despite the best efforts of doctors to elicit an episode of AT, which involved elevating his heart rate to 300bpm for four hours, they were unable to detect the location of the abnormal circuitry.

“Today’s masters endurance athletes are guinea pigs; we are the first generation to be training so hard past age 50 in large numbers,” he said.

After two years of coming to grips with the way he must now live, the 55-year-old Zinn has found that, while he misses doing hard workouts, epic rides, and races on both bikes and cross-country skis, he prefers the person he has become.

“I’m easier to be around,” he said. “I can go on vacations with my wife and be perfectly happy with whatever we do; I’m not pacing around hoping to get out and get some exercise. Rather than being out training or out of town at races, I now enjoy fixing my wife’s breakfast and lunch before her early-morning drive to her job. This new lifestyle is a work in progress, but I think I will be healthy longer.”

TAKING IT TO HEART

The complexities of the heart, the body, human physiology, and genetics make it extremely difficult to predict when and in which heart something catastrophic will take place. Why did this happen to Endicott when it did?

There are 50 years of cumulative variables that would need to be considered to fully understand what went wrong on that cold, crisp day at Devil’s Thumb.

Much of it would be genetic. Did he have a tendency toward higher blood pressure? Yes. What about cholesterol? He was always well below average for that, like many typical athletes, with a sound diet that was verging on vegetarian. Plaque build up? A little, but nothing out of the ordinary. These are the little clues that would be easy to dismiss, but put in combination with his stressful lifestyle, filled with epic endurance events and a somewhat frantic employment schedule, sketch a pastel watercolor of an impending storm on the distant horizon. Add stress, caffeine, cold weather, and that watercolor quickly became an IMAX feature film on dying in the woods alone.

“For years it was like the hints were there in all the studies, and [researchers] always conclude that more research needs to be done. And they’re still saying that,” Endicott said. “I’ve done the research, folks. It happened to me. I’ve had friends that are either dead or alive that it happened to. The research is out there; listen to it.”

Have you ever felt that flutter in your chest? Ever thought, “That’s odd. What was that?”

Maybe you dismissed it. I couldn’t possibly have something wrong with my heart — I’m an athlete. I’m fit. I’m invincible. You wouldn’t be the first, or last, to disregard that subtle blip on the radar screen. Chances are it’s nothing, after all.

But how much is too much? Where is that line? If you have a heart rhythm problem, then perhaps you’ve already crossed that line. Is there any turning back?

“Everyone asks where that line is, and how much is too much,” Mandrola said. “It will never be a yes or no thing. It will always be this gray zone. But one of my takes on the evidence is if you have a heart rhythm problem, then perhaps you are over that line for you. Still, number one: Exercise is good. The endurance athlete who gets this stuff is often over-cooked or over-done.”

For Zinn and Endicott, two of thousands who may have ridden and run their way to a contracted lifestyle, the lesson is clear.

“Few people sharing our mentality will make much of a change based on reading an article like this,” Zinn said. “But if the takeaway is that they can keep doing the things they do but with a much higher prioritization of rest, that stands the most chance of actually saving some people from veering off down the path of becoming a cardiac patient.”

We might know what is too little exercise; we have a good idea what is too much; but there’s a large space in between. And you can never rest too much. Embrace it.

Sometimes, cycling can take us too far.

Understanding heart arrhythmias with Dr. John Mandrola

What are the warning signs for heart arrhythmias?

A lot of the time in athletes, atrial fibrillation begins as premature beats, as just shorter periods of irregularity and you feel something in your heart. If you’re an endurance athlete and you get those warning signs, that’s when it’s time to start thinking about going in and getting your heart looked at; if you’re feeling stuff like skips or jumps of your heart rhythm, you don’t really know if it’s V-tach or AF. The majority of the time, those are not dangerous or life threatening, but that’s the time to get it looked at and at least raise your hand and say, ‘Okay, what is this?’ The problem, though, with an evaluation for an endurance athlete — they go to the doctor, and the doctor has no idea what they do [as an athlete]. It’s tough because 999 out of 1,000 patients he sees don’t do the stuff that Velo readers do. Your reader has to be wise to the fact that a lot of doctors don’t really understand what they do [as an endurance athlete].

What do you tell people that do develop AF?

The first thing that a person with AF ought to do is figure out what company that it keeps, because the first thing we ask as doctors is, ‘What else is going on?’ Is AF associated with heart failure or valve disease, or is their thyroid out of whack, or is there something really wrong medically? So a basic medical checkup and a basic heart check up is the first step.

Then they have to be armed with the knowledge that their lifestyle likely may be playing a role. I’m not saying they have to stop exercising. I would never say they couldn’t do this. But if you’re in AF or having AF, you really don’t have a lot of good options if you want to continue doing what you’re doing; drugs really take away what makes you good at what you do. All the drugs for AF slow you down. They affect your cardiac output and some of the procedures for AF are scarier than the disease itself. [Patients] have to know that.

Why are physicians reluctant to speculate as to why someone develops a heart arrhythmia?

Doctors are trained to see problems in a silo. A doctor will see a patient, but will see him or her as the heart rhythm problem. And that heart rate problem probably came from a part of the heart that had a scar and that needed to be fixed. But one of the things we’ve learned from AF is that you can’t ignore the context — chronic stress and endurance exercise, but it might be high blood pressure or obesity or alcohol. If we ignore that and just try to deal with the problem in a silo rather than as a human being, then that’s one of the reasons why we’re struggling with heart rhythm problems, specifically AF. Whatever we use to treat AF — drugs or ablation — AF can come back. New research is showing that if you look for the factors that are leading to the problem, the patients do better. So I don’t completely think it’s a code of medicine, it’s just the way we’re trained. We’re trained in systems: heart problems, kidney problems, brain problems. And we’re not trained — and I know this is a goofy word — holistically. Specialists see their organ but they don’t see the whole person.

This article was originally published in the August 2015 issue of Velo magazine.

Tweet